Extractivismos, pandemia y otros mundos posibles:

Recuperación económica y alternativas desde las defensoras del territorio en América Latina

About the work of UAF-LAC with women defenders of territory

This is a digital and summarized version of the investigation Extractivism, the pandemic, and other possible worlds: Economic Recovery and Alternatives from the Women Defenders of Territories in Latin America carried out by the Urgent Action Fund, with the collaboration of Catalina Quiroga and Elizabeth López. This publication was born within the framework of the Women and Territories Program that supports women, trans and non-binary people in defense of their territories in Latin America and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean.

Since we began our work to support women’s movements in the region, we have seen the drastic effects of extractivism in Latin America, and how its structure has profound impacts on territories and community life. The relationship between the exploitation of nature and the exploitation of women and feminized subjects is evidenced as a central axis of extractivism in Latin America and the Caribbean. In 2016, we launched the publication Extractivism in Latin America: Impact on Women’s Lives and Proposals for the Defense of Territory to share information related to the impacts of extractivism on women’s lives. Today, we remain committed to contributing to reflections on the issue.

Share

What is extractivism?

Extractivism is a phenomenon based on the exploitation of large amounts of natural resources. It has colonial roots and continues affecting all Latin American and Caribbean countries. Extractive activities have occupied a central place in the economic policies in the countries of the region for several centuries, despite their predatory nature. Extractivism has been strengthened at the cost of damage to nature, communities and their territories, both in rural and urban contexts. There are some key features of extractivism:

It is justified with the discourse of "development"

Based on a political and economic order with colonial roots, extractivism places the idea of development in the hand of countries of the Global North that consume the most, while targeting the countries of the Global South to be producing peripheries of raw materials, such as fossil fuels, minerals and agro-industrial products. Based on the idea of strengthening economies for achieving development, this discourse perpetuates inequalities in the countries of the Global South.

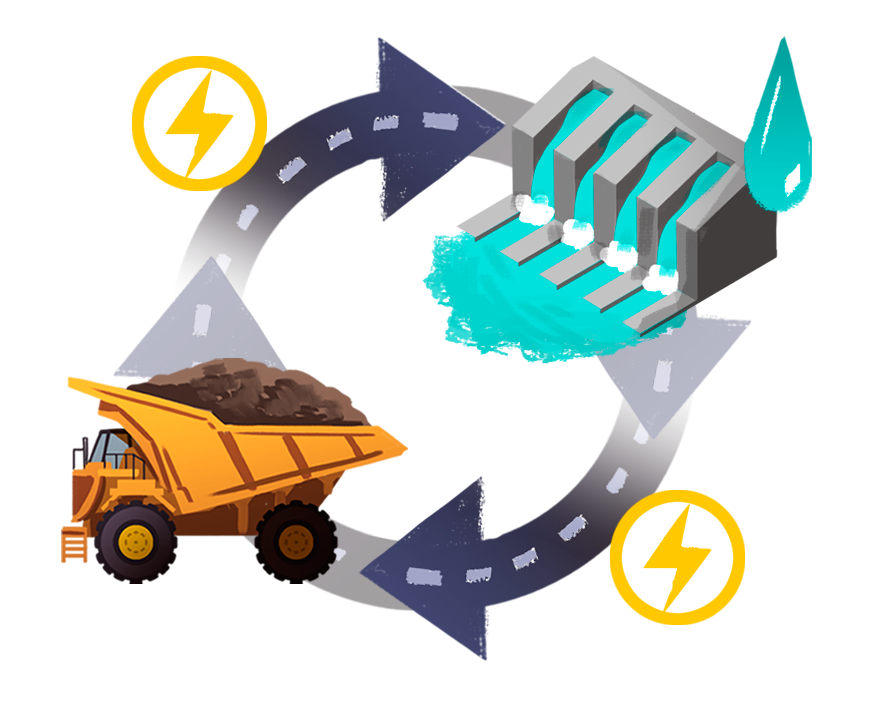

Extractive industries are interrelated

For example, mining requires energy for exploitation, and as a result, much of the energy produced by hydroelectric plants is destined for mining. In addition, mining requires infrastructure for export, while energy production requires infrastructure for its transport.

It "puts a price" on nature

Extractivism fragments and separates nature: a river is no longer a complex network of water, ecosystems, plants and animal species, nor a social, economic and cultural meeting place for a community, but rather cubic meters of water or megawatts of energy.

It implies the imposition of one form of knowledge over others

The most conventional types of extractivism in Latin America

and the Caribbean are:

Fossil fuels

Agroindustry and monocultures

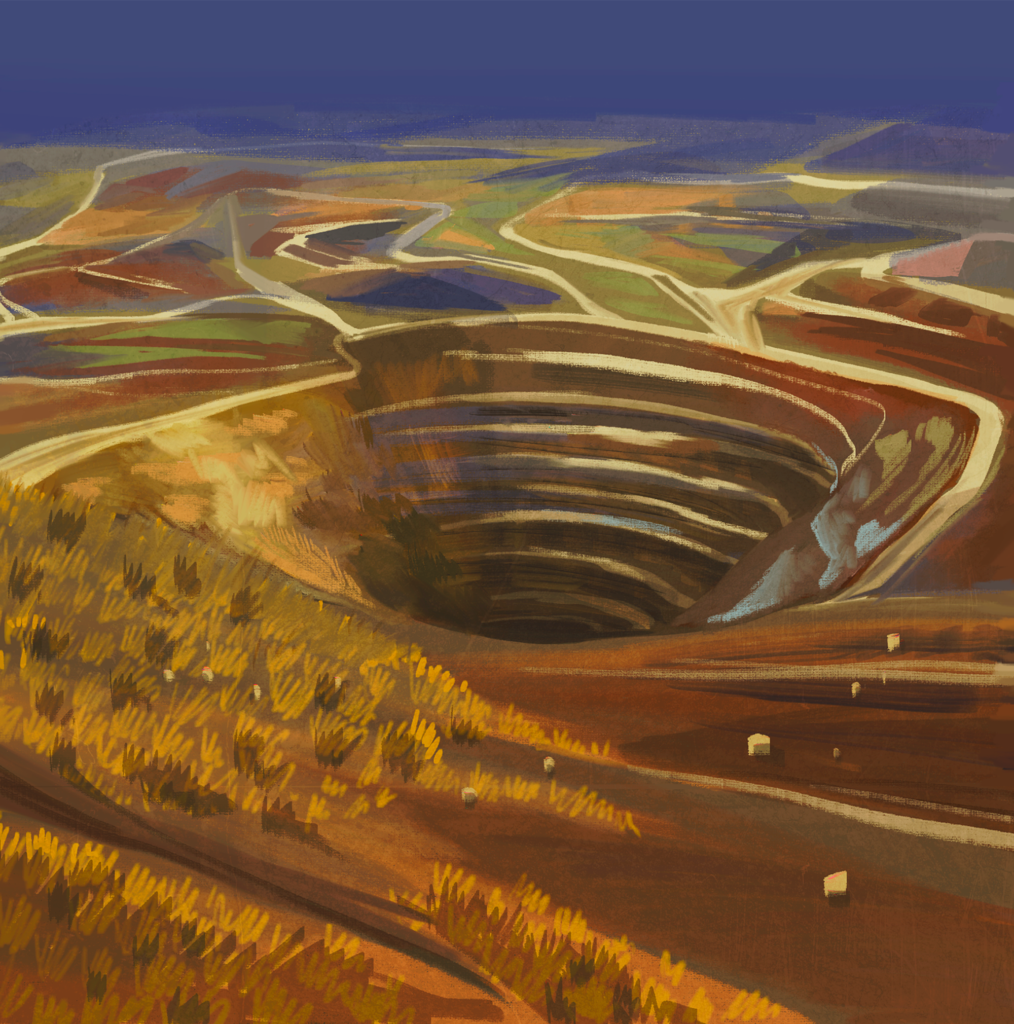

Mining

Impacts of Extractivism on the Lives of Women

Economic insecurity

Violence against women

defenders of territory

Impacts on the health

of women and children

Denial of socio-cultural rights

Obstacles for the participation of women in defense of territories

Experiences of women defenders in extractive contexts

Movimiento en Resistencia a la Minería y el Extractivismo del Carmen de Chucurí (Carmen de Chucurí Resistance Movement Against Mining and Extractives)

Testimony of the companions of the Movimiento de Mujeres de Santo Tomás (MOMUJEST, Women's Movement of Santo Tomás) who denounce that they have suffered sexual harassment, kidnapping, rape and telephone threats for their opposition to the imposition of urban expansion over their land for agricultural production.

Testimony of the Asociación de Mujeres Campesinas y Populares de Caaguazú, Paraguay (AMUCAP, Campesina and Popular Women of Caaguazú Association, Paraguay). There are Brazilian and Mennonite businessmen using planes to spray monocultures of wheat, soybeans, corn, and sunflower for export near their territory.

Asociación de Defensoras y Defensores de la Vida y la Pachamama de Cajamarca (DEVICAPAJ, Defenders of Life and Pachamama Association, Cajamarca)

Asociación de Mujeres Ambientalistas de El Salvador (AMAES, Environmentalist Women's Association of El Salvador)

Testimony of campesina and indigenous women from the Asociación de Desarrollo de Mujeres K'ak'ak' Na'oj (ADEMKAN, K'ak'ak 'Na'oj Women's Development Association) who protect Lake Atitlán, in Sololá (Guatemala), where there is a project to extract the lake’s waters for use by sugarcane agribusinesses.

The Colectivo por la Autonomía/ Saberes Locales (Collective for Autonomy/Local Knowledges), in Jalisco, acts for the defense of collective territories, native seeds and the common good. In 2010, the region was declared an "agri-food giant", which has meant the increased expansion of monocultures.

The socioenvironmental conflicts that derive from extractivism are a dispute between different ways of understanding relationships with nature, crossed by unequal power relations that superimpose one vision of the world over others. To analyze the implications of extractivism in everyday life, it is important to recognize these disputes and the loss of autonomy resulting from its imposition on territories, which result in a series of dispossessions.

“Dispossession is a violent process of socio-spatial reconfiguration, and in particular socio-environmental reconfiguration, that limits the ability of individuals and communities to decide their livelihoods and ways of life. Dispossession implies a profound transformation of the relationships between humans and non-humans that results in restrictions to accessing resources. This often translates into the impossibility of making decisions related to territory, life itself and one’s own body; dispossession is associated with loss of autonomy” (Ojeda, 2016; 34)

In recent years, the climate crisis has led to rethinking the energy matrix and incentivizing the reduction…”. La palabra debería ser “incentivizing” en vez de incentive of the use of energy produced by coal, oil, and gas (decarbonization), types of fuels whose burning is the main culprit of carbon dioxide emissions, the main cause of global warming.

However, without an environmental justice approach, the energy transition proposed from hegemonic technical knowledge deepens the implementation of old and well-known extractive logics given that it requires the use of metals such as copper, cobalt, or lithium to improve the performance of batteries and for circuits that allow efficient distribution of wind, solar and hydroelectric energy.

“Green” extractivism

Industrial monocultures: biofuels and forest plantations

Plant-based fuels such as palm oil sugar cane or corn are presented as alternatives to petroleum-based fuels. However, their cultivation requires large amounts of soil and water, and uses agrotoxins and contaminants for large-scale production it uses agrotoxins and contaminants.

As a result, these monocultures expand the agricultural frontier, displace communities and generate environmental impacts such as soil erosion, contamination, desiccation of water sources and the loss of biodiversity and agro-food diversity.

Forest plantations include the cultivation of timber species, generally non-native, for commercialization and may be related to large companies’ environmental compensation through reforestation projects. Within forest plantations, we highlight the cultivation of trees such as teak, pine and eucalyptus, which are characterized by high water consumption and causing soil erosion.

Hydroelectrics

In 2019, Latin America was the second region in the world with the highest existing capacity to produce hydroelectric energy through the construction of large dams.

With 109.06 gigawatts of existing capacity, Brazil ranks second in the world for hydropower production, after China.

The flooding of often fertile and productive land for the construction of dams has displaced entire communities. Its construction has involved human rights violations throughout the region, including the persecution, criminalization and murder of defenders of territory.

For more than 12 years the communities of Antioquia, Colombia, have firmly opposed Hidroituango, a large-scale hydroelectric project. The project profoundly affected the Cauca River, impacting the living beings that inhabit the water basin and the relationships of the communities that depend on its ecosystems. Likewise, it deepened the dispute over land tenure and increased violence amid the armed conflict, with local leaders suffering threats, attacks, and murders. Such attacks worsened in 2018, the year in which the construction of the dam suffered serious reversals related to errors in the planning and management of risks associated with its construction.

Wind and solar energy production

The production of wind and solar energy is obtained through wind currents and solar rays. Its production has increased in the region: in 2019 Latin America installed 13,427MW of onshore wind power capacity, 12% more than in 2018.

Production of wind and solar energy is structured in large wind or solar farms that occupy large areas of land and require large-scale exploitation of minerals such as copper and lithium for their installation. These metals are key for the operation of electrical circuits of panels and mills, as well as for storage and transport of these energies.

The extensive use of land has displaced rural, indigenous and black communities who, in most cases, are not consulted or considered prior to the installation of the projects. The large footprint of cables and power plants to transport such energies impacts numerous communities along their route. Most of the territories where these projects are installed do not have access to electricity and do not benefit from the implementation of wind or solar farms.

Kichwa women from Sarayaku in the Ecuadorian Amazon are opposed to the exploitation of balsa trees in their territory.

The increase in production of wind energy has had an immediate impact on Amazonian communities, since the windmills produced in China to meet world demand are manufactured using balsa wood because it is a very lightweight material.

Most of the loggers who enter the Amazonian territory to cut down islands of wild balsa trees on the banks of the rivers do so illegally, without permission or regulation.

As a result, violence in the communities has increased, at a significant cost to women, who experience violence to their bodies in specific ways. In addition, the almost total felling of balsa trees in the region has brought great environmental impacts. “In March of last year, all the river basins had an extreme rise, destroying houses, bridges, etc. The river was full of all the branches of the felled trees, which made mobility through the river impossible.

People had to take refuge in the higher parts of the land (…) Apart from that, the balsa tree islands are home to many animals, birds such as the oriole and the harpy eagle, otters”, say the women defenders. The Sarayaku people have said no to the exploitation of the balsa tree, “they cannot enter our territory, the territory needs to be respected. We have been branded as enemies of development, but we do not see a sustainable option in this situation.”

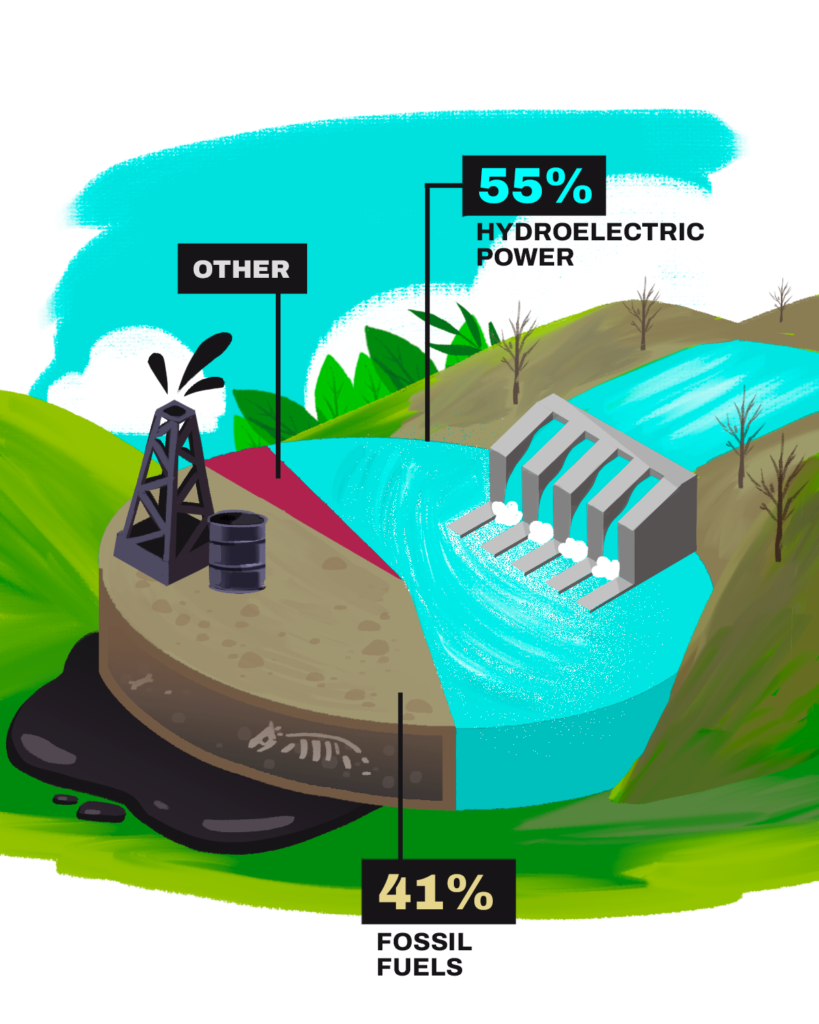

Where does Latin America and the Caribbean's energy come from?

Markets associated with mining, agribusiness and the exploitation of hydrocarbons, as well as the construction of infrastructure, continue to exist and are central to the investment decisions of governments in the region. These forms of exploitation transition into or combine with new “green” tendencies of exploitation, fragmentation and globalization of nature, deepening inequalities and dispossession of communities.

The energy matrix of Latin America and the Caribbean continues to be anchored to two sources: the first of which is hydroelectric energy, which by 2020 contributed 55% of the total energy consumed in the region and, the second, non-renewable thermal energy – energy that is produced by fossil fuels – which in 2020 represented 41%.

Policies and initiatives to mitigate climate change have not resulted in the disappearance of extractive logics, but instead have expanded the boundaries of the exploitation of nature.

Extractivism, in all its forms, is positioned as a key activity for governments, yet its returns are insufficient to consider it an infallible activity for the growth and sustainability of the region’s economies.

The Covid-19 pandemic has intensified the health, social and economic crises that we are experiencing on our planet.

Analyzed through a magnifying glass, the pandemic has its roots in the current economic and production model, given that the possible origin of the pandemic and the difficulties of containing the spread of infection are related to:

the devastation of ecosystems

the prioritization of economic gains over the lives of the population

the lack of access to basic public services, such as health services, for a large portion of the population

In Latin America and the Caribbean, the effects of the pandemic made even more evident the deeply rooted structural inequalities in our region, marked by differences in access to public services between urban and rural populations as well as by class, race, and gender.

New emergencies and vulnerabilities unleashed by the Covid-19 pandemic were added to the direct impacts of extractivism, making it so that actions to resist extractivism coexist and intersect with concerns that this new context has implied in the personal, familial, and community spheres. It must be understood that these are difficult times for women defenders.

We join their voices to affirm that the logic of inequality, which was already operating in their territories prior to Covid-19, explains the high levels of human rights violations in the ongoing period of the health crisis.

How does the Covid-19 pandemic affect

women defenders of territories?

Flip the cards.

Increase in domestic violence

Increase in domestic violence

Violence and fear as devices of state control

Violence and fear as devices of state control

Information as a device of control

Information as a device of control

Structural racism and precarious public services amid a health crisis

Structural racism and precarious public services amid a health crisis

Selective quarantine and economic precariousness

Selective quarantine and economic precariousness

Impacts of Covid-19 in the context of extractivism

Testimony of the Asociación Colectiva de Mujeres Emprendedoras y Solidarias de Tonacatepeque (ACOMEST Entrepreneurs and Supportive Women of Tonacatepeque Collective Association)

Testimony of the Asociación para el Desarrollo Integral de Tejutepeque (ADIT, Association for the Comprehensive Development of Tejutepeque)

Testimony of the Comité para el Desarrollo Campesino (CODECA, Campesino Development Committee), which works for the rights of campesinas and indigenous communities in Guatemala. In the case of women resisting extractivism in Guatemala, militarization brought back memories of the 1980s, when the government committed a genocide against the Mayan people to expropriate their lands and expand agribusiness.

Testimony of the women of the Associação União Quilombola De Araçá Cariacá (Quilombola Union Araçá Cariacá Association), on the Quilombola communities that were not included in the few emergency measures granted by the government as a relief to the economic crisis due to the pandemic.

Testimony of the women of the Asociación para el Desarrollo de la Península de Zacate Grande (ADEPZA, Association for the Development of the Zacate Grande Peninsula) whose territory has been in dispute due to illegal land grabbing by Honduran landlords.

Testimony of La Otra Cooperativa (The Other Cooperative) on the increase in care work in the home for women in times of pandemic.

How do we overcome this crisis?

Governments of the region have already answered this question: they have redoubled their support for extractive economic activities that have done little to nothing to guarantee a dignified life for their populations and have positioned extractivism as an alternative for generating incomes during the health crisis and as a form of economic recovery promoted and designed with the support of large international corporations.

Across the region, activities related to exports, including agribusiness and biofuel production, were declared essential from the beginning of the mobility restrictions in the pandemic. Mining was declared essential from the beginning of quarantines in countries such as Colombia and Chile, while countries such as Bolivia, Peru and Argentina integrated this activity as essential after a few weeks or months of prohibiting it. The inclusion of mining activities as essential in Argentina was motivated by the possible contribution of this activity to the national economy.

The lifting of restrictions on extractive companies is closely related to the economic recovery plans declared by each of the countries in the region. In this sense, the majority of the countries in the region have declared extractive activities to be essential for national economies within the framework of mobility restrictions at some point in the pandemic. In countries that did not declare mandatory quarantines such as Nicaragua, Brazil or Mexico, companies dedicated to extraction continued to work throughout the pandemic, despite the health risk that these activities imply.

Extractive activities and contagion of Covid-19

The continuation of mining during the pandemic put mine workers, their families and communities that surround mining enclaves at risk of contagion. The Observatory of Mining Conflicts of Latin America (OCMAL) (2020) reports that as of July 2020, at least 8,048 cases of infected mining workers had been documented, with 5,000 of those cases in Chile, 1,850 in Brazil, 905 in Peru and 58 in Argentina. There is no similar data on infections and diseases for other countries in the region. Additionally, for July 2020 OCMAL obtained the report of 79 deceased workers in the sector throughout the region. The mining companies of BHP, Glencore and Anglo American presented cases of contagion in Peru, Colombia and Chile (OCMAL, 2020), although according to their pages and international reports they were complying with biosafety protocols to ensure the continuity of production.

Summary of general elements of economic recovery plans in Latin American and Caribbean countries

International Financial Institutions (IFIs) will play a key role in the economic reactivation of the region. These institutions also play an important role in the generation of public-private alliances, as they provide technical advice to countries and private actors, and intervene in the strengthening of business capacities. For this reason, they play a crucial role in promoting extractive projects in the region. Related data points include:

- In 2020, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) approved a total of 45 renewable energy projects in various Latin American and Caribbean countries.

- During 2020, the IDB approved 21.6 billion USD for aid and development operations throughout the region.

- In the context of the pandemic, and in a regional context of social emergency, the World Bank approved 7.8 billion USD worth of financing for 67 operations in the region.

Knowing how IFIs operate and what projects they finance is an important step in territorial defense. FAU-AL, along with other allied organizations in the Count Me In! Consortium, has supported the development of Behind Extractives: Money, Power and Community Resistance, a toolkit that helps grassroots organizations understand and develop strategies that target actors who finance extractivism.

The obstacles imposed by the pandemic are inescapable realities that lead to new reflections on autonomy, self-nutrition, care for life, and the reinforcement of ancestral knowledge about health, in addition to demanding new ways of understanding the collective protection of bodies and community territories and maintaining solidarity as the basis of the social fabric.

From the visible world to the possible world: community alternatives led by women

The collective responses led by women to face health risks and the economic crisis intensified by the Covid-19 pandemic demonstrated their ability to sustain communities and their ways of life in a context of crisis.

The actions to respond to the health emergency proposed by the women’s organizations that participated in this research do not separate the needs of the body from the needs of the collective territory. collective territory. In addition to being a reaction to specific emergency situations, they respond to systems of exclusion and violence via the construction of other forms of life and new social agreements.

Of garlic, herbs, and ginger; health in our hands

In various communities and cultures, there are different ways of understanding health and illness. Collective and ancestral knowledges that communities safeguard related to traditional medicine and its diverse practices were present in the responses of women’s organizations to prevent and provide care during Covid-19.

Women play a key role in the use and spread of these knowledges, since they are the main managers of health in the family context. Facing the pandemic, women turned to medicinal herbs on a daily basis, making a series of recipes and recommendations for the prevention of illness and home care.

Flip the cards.

Colombia

Colombia

Ecuador

Ecuador

Brazil

Brazil

Testimony of the Movimiento Pela Soberania Popular na Mineração (MAM, Movement for Popular Sovereignty in Mining), a national movement organized to resist large-scale mining in Brazil. Women of the organization have generated autonomous and self-managed strategies for promoting, for example, the cultivation of vegetables, intended to generate women incomes and improve family nutrition.

Economic sustainability of women and their communities

Economic alternatives developed by women are centered on the reality of their communities and with a vision of collective benefit and respect for Mother Earth.

In their proposals, individual sustainability is linked to family and community sustainability; they are understood as interconnected networks that seek collective well-being. These alternatives seek to promote the autonomy of women, not only in material terms, but also in terms of decision-making based on their will and independence.

Peru

Peru

Honduras

Honduras

Community mechanisms for communication

Having local and independent communication alternatives is a key factor in organizational processes, such as community health management. In the context of the pandemic, protocols for prevention and caring were developed in many cases by the communities themselves, with information appropriate to their contexts that was shared through local, collective and alternative media.

Honduras

Honduras

Brazil

Brazil

Guatemala

Guatemala

Prevention of contagion and community protection mechanisms

In addition to engaging in actions to protect and maintain their health at the individual and family levels, some communities have implemented collective control and monitoring measures in their territories, installing disinfection points and allowing the movement of only basic necessities. These mechanisms are the result of consensus and reflection on collective protection.

Peru

Peru

Bolivia

Bolivia

Collective care and sustaining resistance

Initiatives for care, well-being and physical, emotional and psychological health are part of the agenda of many women’s organizations, and have occupied a central place in the organizational processes of women defenders of territory.

Care initiatives and spaces serve to collectively regain confidence and self-esteem, and to provide emotional support in different situations of risk and violence that they experience in their personal lives or because of their activism. This integral vision of care also reflects interdependence with the natural environment and the elements that compose it, stemming from a deep relationship with their territories.

Colombia

Colombia

El Salvador

El Salvador

Care is interdependent and extends towards territories as a whole, reflecting the diverse world views and cosmovision of the people. Women defend their sociocultural rights by strengthening their identities and their ancestral relationships with their territories, recovering languages, knowledge from their elders, sacred places and traditional practices for the caring of earth and body.

The initiatives by women defenders of territories in the region are a call to reflect on new forms of activism and resistance, as well as to question the model that led us to the current health, social, economic and political crises. Learning from women defenders’ stories and proposals for thinking about the present and future can show us a way to think about alternatives to build environmental and social justice, and how to deal in a more humane and careful way with new possible crises that we will face as humanity.

Care is a way of inhabiting

and creating possible

worlds, a bet for wellbeing

that women defenders

put in the center of their